Let me start by putting my biases out there, I have fallen in love with this term. It is so simple but yet so powerful and it has been really interesting furthering my knowledge on the subject. Normalisation of Deviance was a term coined by NASA following investigations into the Challenger explosion. There are a number of YouTube videos on the subject and I would highly recommend watching them.

Let’s first examine the phrase ‘Normalisation of Deviance‘ and what it means.

Normalisation: a process that makes something more normal or regular.

Deviance: diverging from usual or accepted standards

The term fits very well with human nature to look for shortcuts and efficiency savings. As humans we are very good at identifying short cuts and rationalising them. These traits easily transfer into Diving.

In diving, we have a number of set procedures and guidelines we are taught to make diving as safe as possible. Now some of these vary from agency to agency, but there are many generic ones, and even the ones that vary have similar underlying themes and reasoning’s. For this example let’s take the Buddy Check. Agencies teach in different ways with different acronyms but the underlying reason is still the same, where the main diving components are checked. Deviance is when divers move away from these procedures for example only completing a quick short buddy check (skipping bits) or not completing one at all. Divers are deviating away from procedures by taking these short cuts. When divers do this, and there are no incidents during the dive, the justification for the short cut is reinforced, and this shortcut is then taken again and again, then starts to become the norm, ‘Normalisation of the Deviance‘. The key phrases heard are, ‘It’s always been fine’ and ‘Never had a problem’.

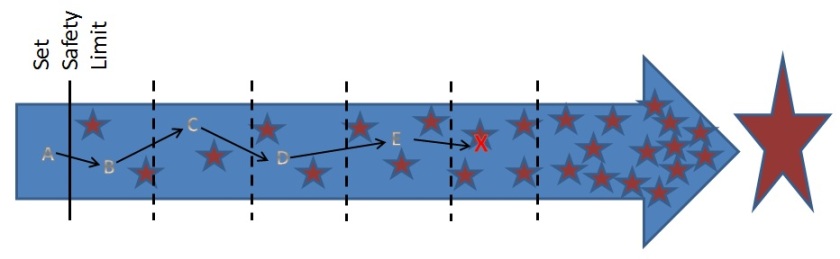

The graphic below is a representation of the scope and dangers of a dive. As it advances the chances of incidents illustrated by red stars increases, all the way to the point where an incident is inevitable. Now as divers it is impossible to know where these incidents sit or will appear, all we know is there is a “safe zone” (for this article I am going to refer to it as the safe zone, but it is not completely safe) where incidents are extremely rare and the various agencies have created procedures to help divers stay within this zone. Depth limits are an example of this.

Now take a diver who ignores/skips one or more of these procedures and moves from point A to point B without incident. After a few dives they personally shift their view/perception of the safe zone along and this becomes their new benchmark as everything has been fine so far. Once a shortcut has been taken, it is human nature to look for the next, and this moves the diver to point C and eventually their benchmark is reset again. This happens in incremental stages all the way along until the diver hits an incident (Red X). At this stage and evidenced in many discussion topics on various online forums, the divers justification and root cause analysis is that it was that last small change they made that caused the incident, that extra shortcut from point E. While everyone else looking in from the outside are not surprised as the distance between being in the original Safe Zone and X is huge.

Now take a diver who ignores/skips one or more of these procedures and moves from point A to point B without incident. After a few dives they personally shift their view/perception of the safe zone along and this becomes their new benchmark as everything has been fine so far. Once a shortcut has been taken, it is human nature to look for the next, and this moves the diver to point C and eventually their benchmark is reset again. This happens in incremental stages all the way along until the diver hits an incident (Red X). At this stage and evidenced in many discussion topics on various online forums, the divers justification and root cause analysis is that it was that last small change they made that caused the incident, that extra shortcut from point E. While everyone else looking in from the outside are not surprised as the distance between being in the original Safe Zone and X is huge.

Now this problem is normally compounded due to the fact that human nature makes us followers in short cuts. What you find, groups of divers move through these steps together almost in their own bubble as these shortcuts become the social norm. When others witness this group, they rarely if at all, point out the issues and more often than not, are influenced into taking the same or similar shortcuts. The cycle then repeats itself drawing in more and more divers.

A common example of this outside of diving is driving cars, how many of you reading this break the speed limit and carry on doing so because nothing happened? How many like to but are careful as don’t want to get a ticket, but when someone comes shooting past, you then speed up to follow them thinking they will slow/be first to be pulled over if there is a speed trap or the police? If you look at the statistics your chance of crashing / causing an accident is greatly increased once you go beyond this speed limit. Drivers then also justify driving fast by claiming to being good drivers, but how many have actually done an advanced driving or high speed course? FYI, I am not admitting to anything and take from it as you will, but I will clarify, I myself are human. 🙂

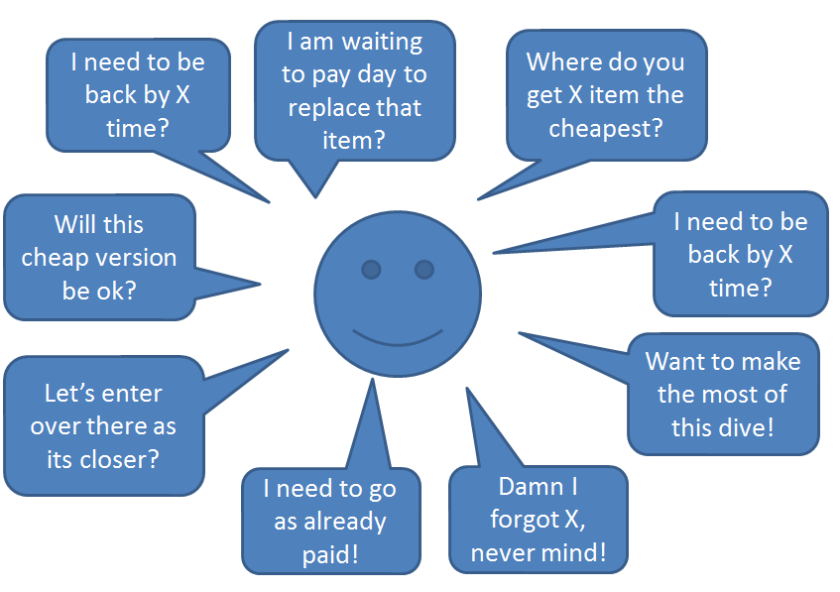

So why do divers do it? There are a number of factors that push / encourage humans to constantly seek out shortcuts. The main one is shortcuts in general are extremely positive, our whole evolution of a species has benefited hugely in the desire to find and take shortcuts and this has led to huge advancements. We are consciously and unconsciously taking shortcuts day in day out. The difference being is the failure of the majority of shortcuts very rarely have any significant impact on us. So as a natural state, it is something extremely difficult to fight and for this reason, it is far easier to fight it as a group then as an individual. The challenge for the group is to fight this urge, otherwise as mention above the group could cause actually swing it the other way. The other 2 big influences are time and cost. We only have a set amount of time to enjoy our diving along with a set amount of cash to fund it. These all play such a huge roll, even when people deny them playing a role in their decision making, they do. How many times have you heard some of the following comments from divers or you have used yourselves?

Now I am not implying these are bad comments to make, as sometimes they are completely reasonable things to say, suggest and do. The point is how the factors above do affect ‘everyone’. I am sure you can also think of a lot more examples.

So how do we tackle this issue in our own diving and diving communities?

First I think it is good to try and categorise these deviance’s, and I think most can fit into 1 of 3 categories.

1) Unintentional Errors (Mistakes, Slip ups)

These deviance’s from procedures/protocols are made by accident, and the diver is normally quick to self-correct themselves initially. However we are very much creatures of habit, and the more the unintentional error repeats itself, the more likely it will happen again and again. We are never 100% perfect, but one way to help this is with notes/check lists. For example making notes from a dive briefing will help cement the information further, or having a setup check list. Aviation/Pilots are a great example for this, even if they have been flying the same plane for years, doing multiple take offs/landings each day, they still work through a check list.

2) Risky Behaviour (Risk is underestimated or believed to be justified)

This is probably the most difficult ones to tackle or recognise as everyone’s view/estimation of risk is different, also the level of risk is greatly influenced by a divers skill set. These deviance’s are the ones that slowly build up over time, and therefore are the more difficult to tackle. I touched a little bit on this in a previous blog:

https://grahamsavill.wordpress.com/2017/08/05/better-way-to-dive-to-be-a-better-diver/

3) Reckless (Disregard of Risk or Negligence)

There will be multiple deviance’s away from many if not all protocols, and the diver will have little to no regard to the dangers or consequences of this. Divers who fall into this category will unlikely listen to reason or believe they know everything anyway. The good thing for other divers is, this is very easy to spot, and our human nature is to stay away from risk, so we naturally try to distance ourselves from these divers. Most of the time the only way for these divers to change their view is when they are confronted with an actual incident. As nothing can convince the divers in question, it’s important to highlight the issues to new divers who maybe listening/watching so they are not influenced by bad practice.

Next step is to decide in our own dive groups what our procedures and protocols are. The great part here, is the majority of the hard work has been done for us by the various agencies. Now as mentioned above, these protocols can differ from agency to agency and it’s up to the group to decide which one they follow.

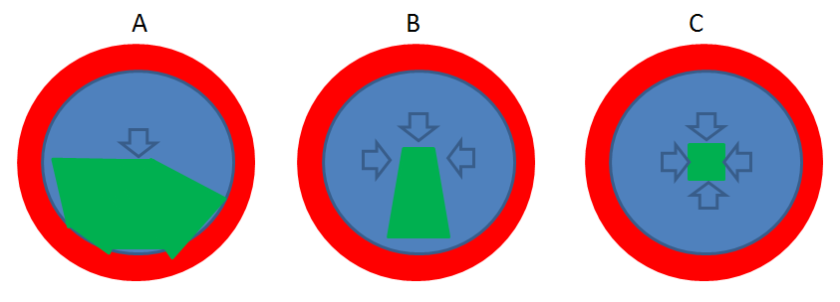

If we look at the graphic above we have 3 groups of divers A,B and C. The red area indicates the danger zone where incidents turn major, the blue is the safe zone, green represents where an incident could progress to, and the arrows represent protocols. These groups are not definitive, and are based more on a spectrum, so would say these represent the two extremes and the middle of that spectrum.

Group A, are following the very basic of protocols if any at all, and in an event of an incident, it can progress and escalate in a number of directions, as each diver will have no real indication how the other divers will deal with the situation. You see this regularly on dive holidays where you have a number of divers who may have never dived with each other before, who get a basic dive brief, then follow a guide around a dive site. Here you find only the simplest of protocols have been discussed or addressed.

Group B, have a number of protocols in place but differ slightly. When an incident occurs, majority of the incident is contained by these protocols and there is only a small area in which the incident can evolve outside of their protocols. This is where the majority of regular divers sit who have regular buddies, they have a good understanding of what each of them will do in an incident and would have the majority of protocols covered. However things will be different from diver to diver which will change their response to an incident such as the equipment they are using (Singles, Sidemount, Twinset, Rebreather, BCD v Wing, Spool v Reel, Different Gas Mixes etc).

Group C, have very strict detailed protocols in place, and when an incident occurs, taking out the human factor, their response will be exactly the same. This means the chance of the incident evolving is limited as much as possible (just to note, this does not mean it is impossible, just less likely). This was very much the DIR (Do It Right) philosophy, where they went with protocols such as matched equipment setup, out of gas, specific gas mixes etc.

Now you have a better understanding of these groups, have a think about some of the following incidents and how the divers in group A could all do something different when the incident occurs and how that could impact the incident by making it worse. Out of Gas(Primary/Secondary Donation), Separation, Dive Time/Depth Overrun, Poor Communication, Entanglement, Loss of Viz, Group Position in the water.

The size of the group plays a large part and I see a lot of debate around how many divers should make up a group, from people claiming diving solo in a group, to others saying buddy pairs, and Tec divers claiming teams of 3. As the vast majority of divers sit in groups A and B, imagine the possible issues as more divers are added to a group incident each with their own individual protocols. For these groups buddy pairs are certainly the better way to go and is the reason many recreational agencies promote this style of diving. Now let’s take group C, imagine if the additional divers follow the exact same protocols and an incident occurs, having an extra 1 or 2 divers would certainly help and actually become a must have as you pursue more and more challenging dives. I want to take a quick moment to mention a gripe I have about people who talk about diving solo in a group of divers, overall which group above do you think that group is as it is clear they have different protocols? I also touched on this topic in a couple of my other blogs the one linked above and https://grahamsavill.wordpress.com/2017/10/07/diver-stages-from-reliant-to-contributing/

So to finish off this blog I wanted to leave you and your group with a few questions to consider the ‘Normalisation of Deviance‘ in your diving.

- What behaviours and conditions do you accept and dive now, that you previously would not accepted?

- Is all your kit maintained and serviced in line with manufactures recommendations?

- What shortcuts do you find yourself taking?

- Which rules do you change/flex so you can do that dive?

- Do you do in-depth analysis on what could have gone wrong or use Success of a dive to define what is acceptable?

- Do you focus on the incident that happen/nearly happened or what behaviours/protocols that were seen as acceptable before the incident?

- What changes have you made to the procedures you were taught as experience tells you these changes were fine to make?

- How does your group deal with members who raise issues/concerns?

I hope this blog has come across as informative and you have enjoyed my take on the subject. As always, I would love to hear others thoughts on the subject.

G-Sav