Author: Graham Savill (G-SAV)

Snorkel No Snorkel??

A few posts jumped up recently around snorkels, which kicked up the usual debates between the opposing sides. So in this blog I wanted to share my thoughts on the subject, as well as giving a few hints and tips, with one MAJOR ONE I think EVERYONE should understand, practice and spread the word about. If you are going to read or not read any of this blog, please read the tip below.

The Major Tip:

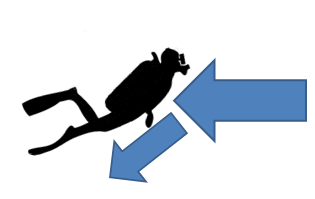

The majority of us, would have been taught how to clear our snorkel by expelling a breath after diving down below the surface. Now this technique does have a place in courses, as it builds water confidence and teaches how to clear water from a snorkel should water enter it, but that’s as far as I see it. The issue is not with the actual technique of clearing, it’s what happens leading up to it. The snorkeler swims along, takes a deep breath, pivots, swims down keeping the snorkel in their mouth, swims along at a given depth before surfacing. The issue is leaving that snorkel in their mouth! If for any reason they pass out (possibly following hyperventilating) the water now has a clear route down the snorkel, into their mouth, and straight down into their lungs. If this happens they WILL experience drowning. They might not pass out, it could be shock for example. Now, if they remove the snorkel, their mouth is closed, and with the face mask protecting their nose, the chance of water getting into their lungs is greatly reduced. So the chance of drowning is greatly reduced (but still possible). If you snorkel and like to dive down, get into the habit of taking your snorkel out.

Snorkel or No Snorkel?

Now as always in my blogs I do like to make my own views clear, and this one would be no different. I ditched my snorkel shortly after training, and having one could have been handy on a number of occasions since then, but was not absolutely necessary (I managed to grind my way through). This confirmed my own conclusion, one was not needed. I lived and debated this position for a long period of time. This was mainly down to not knowing what I didn’t know, which is a subject I blogged about recently and would recommend having a read as it highlights why so many divers can grasp on to incorrect ideas. You Don’t Know What You Don’t Know!

On my journey of re discovery and aiming to be the best diver I could be, I started questioning all the various conclusions I had and was adamant about. I do have a competitive nature, and I do love a good debate, and have always loved trying to argue from what I believe was the devils advocate position as it’s good fun and a laugh. So when looking at this question, I looked at one of the most common reasons given about not using the snorkel, and that was around proper gas planning and management, which would mean a snorkel is not needed. Now for those who are not that into debates, one of the strongest attacks of a debate is to as quickly as possible take the opposing sides argument off the table, build on that premise, and other bits will fall into place. As soon as I did this, I realised my argument for not having a snorkel was not as strong as I once thought! So now I sit on the side of there are a number of dives that taking a snorkel could be very beneficial. A lot more than dives where a snorkel is not necessary.

So taking the properly planned gas management argument and getting rid of it. There are few instances where as a rescuer it will be beneficial to remove your kit. This means you could have a full tank of gas but it will be of no use to you as it will be more of a hindrance. A couple of examples, you are towing an unconscious diver in from a shore dive, the waves are breaking between between 30cm to 60cm (1-2ft), depth 1 to 1.5m. Working your way through the white water will be extremely challenging with full kit, even without kit the chance of falling over, getting knocked around etc is extremely high, and will be a lot worse with kit on. Only real option is to remove your kit. This needs tp be done soon as possible and once off it would certainly be better and safer for you to have a snorkel in. Staying on the task of rescues, a similar instance can occur getting someone on to a boat, jetty, rocky shore line, where the removal of kit is paramount. Now I am not saying some cant be done in full kit, which some can. The point of this is to highlight that the other sides argument cant be applied fully. Staying in full kit, is not impacted in anyway to you having a snorkel in your pocket.

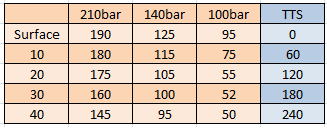

Now keeping on rescues, lets say your buddy loses their gas due to something outside their control, free flow or bust hose. I have seen brand new hoses go pop, so having new hoses certainly wont make you immune from this happening. Anyway you buddy breath and get to the surface with that 50 bar reserve, perfect planning! Now tensions will be raised due to stress, and both divers could be breathing up to 100-140 ltrs a minute at the surface, possibly more. (To learn about breathing rates, check out Gas Management and Planning). At the lower end rate, that will only give you 6 mins of gas at the surface, higher end maybe 4mins or less. You have a few issues arising out of this if the sea state is not perfect (in the UK it rarely is). 1) you need to stay connected to your buddy as you don’t want to drift apart and pull the Reg out, this means you are now exerting energy holding each other which equals burning through gas. 2) Due to swell, you are now likely to bump into each other, increasing the risk of injury. 3) Conditions will mean the boat is slower picking up divers, as again they don’t want to rush and cause an injury, meaning longer wait times in the water. Again this can all be done without a snorkel, and you could battle through without one, but again it certainly would be safer and easier with one to hand. There is also the challenge, if you are already on the boat and de-kitted, and you have to jump back into the water to assist in a rescue, a snorkel could certainly help in that instance.

Taking a step a way from rescues, here are a few more examples, I could come up with. Sometimes we complete multiple dives a day on twinset configurations, and knock out 2 or 3 dives on 1 fill. If you are planning to do this, you will want to conserve your gas after the 1st and possible 2nd dive. So rather than using gas at the surface, you could switch to a snorkel, and save the gas for your next dive. In the UK, the water gets cold especially during the winter. This means you have a greater chance of free flow if breathing your reg on the surface, which if not resolved could result in loss of gas, or having to shut your cylinder down. I did do a blog on free flows here Free flows – Every Second Counts

There are a number of other instances that could increase your wait time at the surface which no amount of gas planning could account for. Sea Mist/Fog could come in. The dive boat could be taking its time as it’s dealing with a rescue. Every year we hear of lost divers or the dive boat not actually being there. Some shore dives require long surface swims. For me, my thoughts are switch to a snorkel and keep my reserve gas as back up.!

With all that in mind, I believe for the majority of dives a snorkel is piece of equipment that is well worth having to hand. There are of course dives, where a snorkel will make no difference. I personally do not carry a snorkel on every dive, but there are certainly dives where I have left it behind and it would have been wiser to have it with me.

Even tho, I have shifted into believing carrying a snorkel is the wiser choice, I am certainly not an advocate of keeping it attached to the side of your mask. Leaving a snorkel attached to your mask adds a number of potential issues. First is it becomes an additional entanglement hazard. I have personally seen someone get caught in a fishing net because of their snorkel, and have seen numerous incidents where divers have launched/towed a DSMB that have also become entangled. 2nd it causes clutter. Now what I mean by that, is it’s a piece of equipment out in the open that is not being used, so has no reason to be there! Clutter can cause nuisance or confusion. I have seen this with newly qualified divers confusing it with their regulator or even their BC inflation hose. So where do I stow mine, well, I have a simple silicone collapsible / folding one which goes either in a pocket, my get out of dodge bag (My GOOD Bag (Get Out Of Dodge)), or tucked away somewhere. I also went for a bright colour rather than black so it differs significantly from my BC hose.

As always I hope you enjoyed the blog, and would love to hear others thoughts on the subject.

G-SAV

Courses, Agency, Experience – What does it all mean??

I originally started this blog tackling a theory that many divers hold, that Advance Open Water and Rescue Diver are high level courses. While I will get into explaining my answer where I believe these are only basic skilled courses, I also found myself commenting and sharing my views on a couple of other comments I regularly hear and read; “Which agency is best?”, “It’s all about the instructor?” And “You need to gain experience first”.

Now this is not an Agency bashing post and I am going to stay away from commenting on specific Agency names. I will use some common course names, as the majority of divers will recognise the level I am referring to. I did just try writing this blog using terms Level 1,2,3 etc but it was difficult for me to even keep track of what I meant. So when I talk about ‘Open Water’ level, this is also known as Open Water 20, Ocean Diver, Scuba Diver, Club Diver etc.

Agencies:

Normally when people talk about dive qualifications, one agency is known above everyone else! Sometimes people can name a small handful. However many are shocked to understand there is over 150 different agencies (Some of these are linked as there are some parent Agencies, with offsets under them).

At the very top is the WRSTC (World Recreational Scuba Training Council) and many of the agencies work with this council. There is also CMAS (Confederation Modiale des Activites Suaquatiques) which was actually the first under water diving organisation setup in 1959, which does something slight different. Now the WRSTC mission is to set MINIMUM training standards an agency must meet to qualify a scuba diver. Many people believe they set the standards an agency must follow! This is incorrect an agency is able and it’s in own right to set higher standards than the minimum set out by the WRSTC.

A phrase I hear commonly is, Agency does not matter it’s all about the instructor. While this does have some underlying truth to it, it is very far from a truthful or informative statement. How I see it, agencies fall into certain categories. Below I have tried to split these out in a table below. This is not a definitive list as some agencies can fit into multiple categories, but more a way to show how agencies can have very different missions and goals.

| Professional Recreational Agency | These are agencies that predominantly cater to professional recreational dive instructors. These courses are very much structured to offer courses that can be delivered in a set time window. These courses are normally broken down in to chunks, allowing customers to choose what they want to learn, but also assist the instructor in making a living from selling courses. |

| Club Based Recreational Agency | Club agencies are there to cater mainly for volunteers and groups of divers who want to get together and go dive as group. Courses are normally longer, contain more content with the idea of it being delivered on a continuous basis alongside normal club diving. Their specialities consist of courses to enable the club to go dive such as Chart Work and Boat Handling. |

| Professional Technical Agency | Same as Professional agencies above, but focus what they class as Technical Diving courses |

| Club Based Technical Agency | Same as club but focus what they class as Technical Diving courses |

| Professional Tec to Rec Agency | In recent years a couple of Technical Agencies have expanded in to the recreational course arena, and have added a slight twist by bringing some of the skills and disciplines of Tec diving into their recreational courses. |

** What contributes as a TEC course can vary greatly between agencies. There are club based agencies out there that teach things such as decompression diving and twinset in their recreational program!

This table also does not mean all the agencies in a group are the same. If you take the Professional Recreational Agency group, there is a range between the agencies in the standards they set and the content of their course. So my advice is investigate the different agency options available to you, and work out which ones best suit your needs. Then aim to find a good instructor in that agency. Now you might find a great instructor who only teaches in your 2nd or 3rd choice of agency. This will then come down to a decision only you can make. If they are miles ahead, then go with the high quality instructor. Keep in mind, there is nothing stopping you switching agencies and instructors. It’s something I would suggest every diver does, as each Instructor, Agency and Course has it’s pro and cons. Take me for an example, I write these blogs and I try and share as much of this information in my teaching and diving as much as possible. There will be a time, where I have passed on the majority of it and the students learning curve will flatten off. If they want to continue getting extra knowledge above and beyond the course material then going with another instructor will open them up to a completely new set of ideas and views.

Agencies can also play a big part on how the instructor teaches with some having a lot of restrictions while others very few. Restrictions are not always a bad thing but they are not always a good thing. The level of support from Agencies also differs substantially. This can impact the normal courses as a consumer, but if you are looking to go Pro can have a big impact on your choice of agency.

So what makes a good instructor and how do you recognise one? That is going to be a fairly long blog for another time. Until I get round to writing, there are blogs written by others you might want to check out, as well as ask in the various social media forums.

Courses:

Now one of my pet peeves is course names, and I covered why in my blog You Don’t Know What You Don’t Know. While the course names have been a fabulous marketing strategy, it has breed a misunderstanding of the level of the course and who should take it. This has also been amplified by schools and agencies using this misunderstanding in sales pitches which has continued the cycle.

I see courses fitting into the following categories, again this might cause some debate, but it’s mainly to show how my thought process as formed.

| My Category | My Take on My Category | How I think Courses fit into My Categories |

| Foundation | These courses lay a foundation of basic skills a diver needs to operate underwater. Many of the courses out there do not adequately equip a diver to conduct all but the simplest of dives. By this I mean going diving with an equivalently trained buddy independent of a school or club, basically going off by themselves. | Try Dives, Discovery Scuba, Scuba Diver, Open Water etc. |

| Core | Core skills are separated in many professional agencies across multiple courses. To me, all divers who want to go dive should have these key core skills and knowledge to dive safely and deal with the majority of issues that arise. I see these very much as core skills not advanced, and every diver should have them. | Advanced Open Water, Scuba Diver 2, Rescue Diver, Sports Diver, Navigation, Boat, Drift, First Aid, O2, Enriched Air, Master Scuba Diver |

| Professional | These skills focus around safely conducting and providing training. It’s about managing groups, courses, as well as a business. While these will improve a divers skills, unless you are actually going to progress into being an instructor, there are many more Advanced courses out their which will improve your diving. | Dive Master, Asst Instructor, Instructor |

| Advanced | These build on core skills and opens them up further and in greater complexity. While not required in recreational diving, it certainly can make a huge difference. The main focus for these courses is the more in depth planning, tighter controls & processes, and task load management. I have added ‘Deep’ as to me this requires advances skills to truly dive safely at this depth, however it is poorly taught in my view. I also * rebreather has with costs coming down, I think in the future, more recreational rebreather courses will be available for brand new divers skipping out open circuit completely. | Deep 40, Deeper 40+, Twinset, Side mount, Decompression, Overhead, Rebreathers**, |

| Expedition | These types of courses, focus not just on the in water logistics of complex dives but also all the logistics on making those dives happen. It’s not about putting a few divers on a boat and going somewhere, it is about the researching a unknown location, gathering info on and planning routes. Conducting a project such as clearly mapping a cave system, or recovering large artefacts from ship wrecks. These are also conducted in the more challenging environments and locations. The skills learnt are very much around the very large picture. | Advanced Diver, First Class, Cave, Mine |

| Special Interest | Not everyone likes taking photos, not everyone is interested in fish. There is a number of these that divers in the community look down at, and this is normally for a couple of reasons. Instructors offer these to keep turning over courses and only cover the minimum standards. If there is something you are interested in, find an instructor who really has a passion for the subject and the course will be extremely worthwhile. | Marine Life, Photographer, Search & Recovery, Wreck, Dry Suit |

There is not a direct link between course level and the quality of the diver. The same with number of dives, even two equally qualified divers with the same number of dives can be miles apart in terms of quality and knowledge. However on average the more courses someone has done and the more dives, does lead to divers being of greater quality. To put some perspective on that, let’s you have a scale of 1 to 100 on the quality of diver, the difference in the above could be 5 or 10 points, meaning there is a clear difference, but we are not talking either end of the scale. Again there are exceptions such as divers who have only done a couple of courses that are better than divers who have done loads. This is down to the level of tuition provided by the instructor and the divers only natural abilities.

The only way real way to improve is through structured learning; courses, workshops, perfect practice and research. Imperfect Practice, no practice, assuming cause and effect, all do not lead to great improvements. So the idea of just going diving is greatly going to improve you diving is a misconception, it will improve it very slowly compared to the efficiency as seeking knowledge and skills from an instructor or mentor. For example, a common question people ask is how to use less air and the majority of responses are based on an incorrect assumption of cause and effect on how we actually breath, rather than the actual correct answer that its in related to exertion. I did a specific blog on this subject How To Use Less Gas While Diving.

I am going to jump right in at the so called ‘Rescue Diver’ level as this has come up recently in the various forums. There seems to be this belief in the diving community that Rescue Diver is somehow an advanced course and you should really have more experience before you go do it. My first response to this, is Rescue Diver does not actually qualify you to do anything more in terms of recreational diving. The course is there to teach skills on how to mitigate risk, be more self-aware of your diving and those around you, and how to safely rescue a buddy or diver if need be. To me this course content will greatly increase the safety of diver, and if they are able to pass the skills and knowledge tests, why would someone stop them from not taking it just because they only have 10 dives? I would rather dive with this person, than someone who has had no experience on any rescue skills. Now rescue diver does qualify you to assist and act as a rescue diver on courses, where having a decent amount of experience under your belt is ideal. However the choice of rescue diver comes down to the instructor, and many will only select a rescue diver they believe is capable of being one to a group of students. This is where experience will come into the decision. That’s not saying there is bad practice out there and there are instructors who will use an inexperienced rescue qualified diver to ensure a box is ticked. I have a similar issue, of people suggesting getting more dives in before taking their Advanced Open Water, when there are clear skills that would immediately make them a much better and safer diver. My other challenge is if someone qualified 10 years ago as a Rescue Diver, not been involved in any rescues, not practice any, then compare them to someone who went through the course last week!

Carrying on the ‘Number of Dives’ stipulation, I believe this is an absolute must for Professional Courses. You need the experience to understand how everything in diving ties up and have the knowledge to answer the huge range of questions put to you from students. You also need to understand the conditions and site, so you can ensure the maximum safety of your students. I have seen a couple of instances of instructors taking newbies to a site they did not, and this shift the instructors attention away from the student and on to the site. A diver should have a decent amount of experience in number of dives and a variety. The knowledge is not what impacts them and their buddy as divers like core skills would give! This is about gaining experience on how things affect others, so they can easily identify trainees strengths and weaknesses and how to best support them. I do have some concerns around ‘No of Dives’

- It’s done on an honour system so anyone could fudge their dive statistics.

- No of Dives does not equal scope, this means someone could do the same dive over and over to make up the numbers.

- The required No of Dives is sometimes too low in my view.

I think professional levels should require a greater number of dives, and have some stipulation about diving in different environments (Boat, Shore, Drift, Night/Limited Visibility, Cold Water, 20m+ Range, 30m+ Range etc.).

Expedition courses should also have the same and from my knowledge they all do, as divers need to build up that knowledge and experience of real world situations. For Advance courses, I think it depends on the course, but most are broken down to different levels anyway.

Experience:

Now with everything I have said above, I am not dismissing experience. Experience can play a huge part in scuba diving, as long as divers learn from it. I see a couple of real issues in the dive community, close calls are laughed off and not really discussed and excuses are made. When people do share their incidents in wider groups, rather than a discussion taking place, what you find is finger pointing and grand standing. How are these divers, who are showing a willing to learn, going to learn when other divers just attack them, rather than working through the problem with structured solutions? Debriefs are just as important as briefings, as it gives the opportunity for everyone to reflect on the dive. By missing this out we could be normalising deviance, and embedding bad practice. Another blog plug Normalisation Of Deviance. To learn from a dive, it does not need to be a bad dive, even looking back at a good dive and really understanding why it went well can be just as enlightening than a bad dive. The key is to be open and supportive, as everyone can have a bad dive, and anything can go wrong. I have a recent example which happened the other day! There is a fairly advance dive I do maybe 10 times a year and I have dived it for a number of years. This year we have been blessed with some awesome visibility which has been amazing and made the dive less challenging. Over the course of a dozen dives, confidence grew and I started to forget how challenging the dive normally is. Then we dived it last week, the viz was poor, and it became a very challenging dive with a close call. Yes we did have a giggle about it after, but we also had a very serious in depth conversation about what happened, what we did that lead to the challenges we had and what we could have done differently. It also made us go back and review our planning. Our overall plan has not changed for the dive, but we have certainly added further detail to it and added some more what ifs solutions. This was stuff we hadn’t planned as previously they were totally unknowns (Just to point out, I am not aware of anyone else who does this dive, so it’s not like there is additional knowledge readily available). The experience gained and learnt will certainly now shape future dives at this site, but also can be used elsewhere.

As always I hope you enjoyed my ramblings, please check out my other blogs as I do try and vary the subjects.

G-SAV

Note: Thanks to Kosta Koeman for reviewing this for me, and giving me a couple additional points to add.

You Don’t Know What You Don’t Know!

There are a lot of blogs out there around diving, skills, handy tips etc. There are not many that actually focus on the Psychology of Divers and Diving. I started directly commenting on this in my blog Normalisation of Deviance, but have lightly touched on it in many others so please do have a read of them. In this blog I wanted to concentrate a little on cognitive bias, and focus on two psychological phenomenon’s which are commonly known as ‘The Dunning-Kruger Effect‘ and ‘The Johari Window‘. After going through my own learning curve, which I am still on, plus watching and listening to other divers, I think these clearly highlight some of the challenges we face within the diving community.

Dunning-Kruger Effect

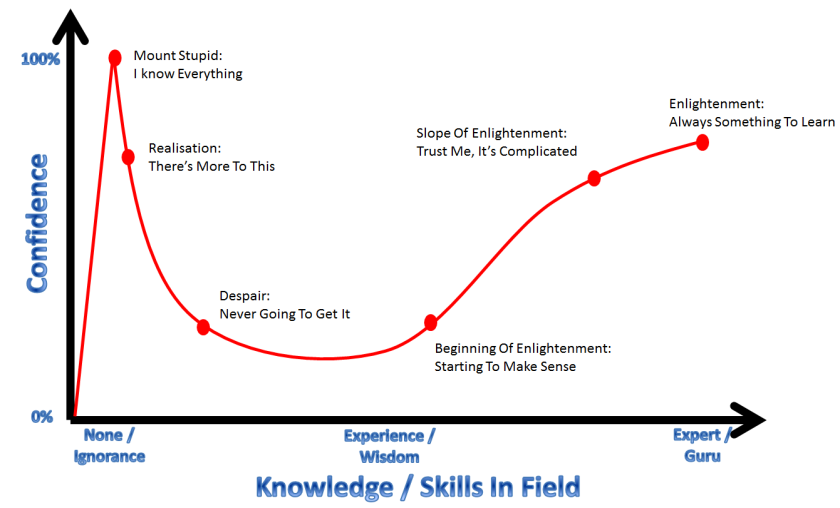

In 1999, Kruger and Dunning did a study looking at the phenomenon of illusory superiority, ‘Unskilled and Unaware of It: How Difficulties in Recognising One’s Own Incompetence Lead to Inflated Self-Assessments’. I am sure now everyone reading this is nodding their heads, as some names/divers immediately jump to mind. I am not going to delve into their research, but simply comment on their graph below and how I see it relates to diving. If you are interested in this, there are plenty of articles and videos online, and I strongly recommended looking into them. They go a lot further into the psychology of the studies and findings.

As I mentioned in previous blogs, I have been through this personally! I think personally overall I am somewhere on the Slope of Enlightenment as there is loads I still need to learn and recognise its more complicated the more I go on. Before you ask, yes at one time I was at the very peek of ‘Mount Stupid’ I had 100% confidence in my knowledge and ability. I look at back now and realise how little experience or wisdom I actually had. This very much takes me back to one of my favourite quotes I heard from another diver, “At 50 Dives I thought I knew Everything! At 250 I realised how wrong I was!“.

This phenomenon is very common and everyone goes through it in one shape or another with everything they learn. This is certainly not helped in the diving community by the course names many dive agencies use in recreational diving! The marketing has been excellent in this sense, as they promote superiority which artificially lifts that confidence. ADVANCED Open Water, SPECIALIST subject, MASTER Scuba Diver, Dive MASTER, PRO Diver. What is interesting, is in what I have witnessed, is ‘Realisation’ has normally come when divers have either shifted from ‘Recreational to Tech Courses’, ‘Shifted Instructor/Agency’ or become an ‘Instructor With Organisational Responsibilities’. Just to clarify that last one about instructors, yes all have responsibilities, I am more talking about lead instructors, who have to do all the planning and organising, have their names on the line if something goes wrong, not the instructors who turn up, follow a plan, teach, then leave. This is also a generalisation as there are divers who fall outside of this who have shifted a long this curve as well as divers who progressed their training but are still camped out on Mount Stupid.

So how do divers move along and become better, more knowledgeable divers? In my blog Better Way To Dive, To Be A Better Dive I touched on some physical things you can do and questions you can ask yourself about your own diving. Staying on the psychology side, I now want to introduce the second part “The Johari Window”.

Johari Window

Luft and Ingham created this technique in 1955 to help people understand relationships with themselves and others. Since then, it’s been successfully used in helping people improve their learning, knowledge and skill set in various subjects. I personally think this is a great addition to Dunning-Kruger Effect, as it gives a way for people to identify their blind spots and take action to make those spots smaller ‘REALISATION‘ in the Dunning-Kruger Effect. Again there is loads of information out there to read and if this is something that interests you, definitely do some research.

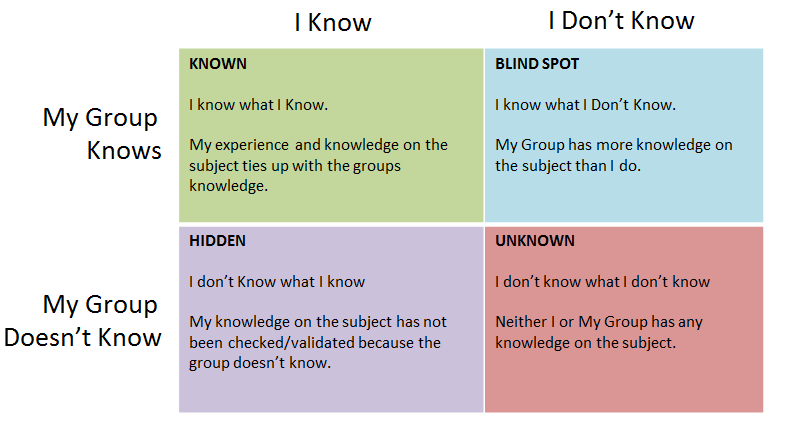

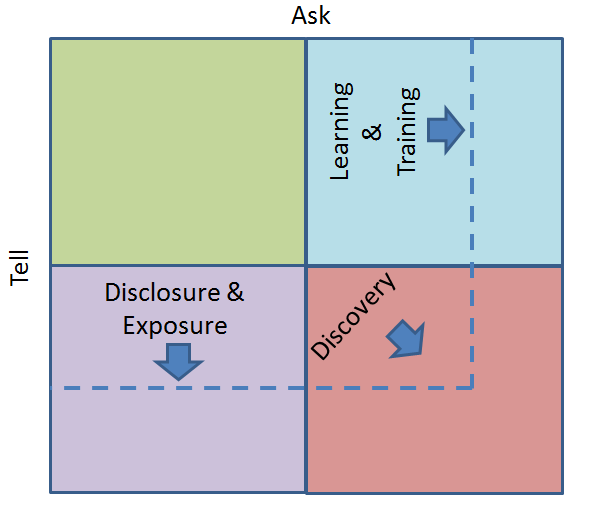

Below is a version of the Johari Window, I have created for divers. This is what I have come up with, and I am sure there are a number of different ways this could have been done, and most likely better ways too (I’m no expert). This is for me to get my thoughts across in a graphical way that I hope many will understand.

So what does this all mean? There are 4 areas of the window, which compares an individual’s knowledge to the groups, along two axis. From Left to Right we look at the individuals knowledge, where Top to Bottom looks at the groups knowledge. As to be expected the group has knowledge which it shares with the individual, making it commonly KNOWN. The group can also expect to have knowledge the individual doesn’t, and the individual will recognise this exists but cannot see it full to understand as it is a BLIND SPOT for them. In contrast to this, the individual will have some knowledge the rest of the group does not have, so will be HIDDEN from the group. Then last there will be the UNKNOWN, neither the group or individual will know about this. The group I am referring to in this example is, the divers you dive with regularly and even incorporates the Agency / Instructor you always use.

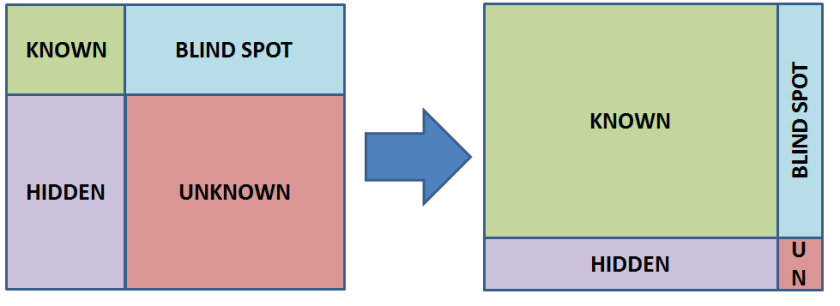

Now when we start something new, the areas of the window are different sizes, with the KNOWN being relatively small. The challenge is not to assume and believe that the KNOWN area is larger than it actually is otherwise it will lead you up Mount Stupid. To progress in anything we must increase the size of the KNOWN area which can only be done by reducing the other areas down.

To make this change, we can concentrate on a number of areas, and with the right actions, motivation and desire to change, these areas can be reduced. Below is the graphic highlighting how this can be done.

One thing to be mindful of is, you will only ever be able to increase the size of the KNOWN area by a certain amount within your group. Once you have approached that limit or near it, focus should be made on how you can expand the group or select a different group. Changing buddies, Instructor, Dive School, Agency or the fabulous invention that is Social Media (said with a little bit or sarcasm). Now, what you know may not be correct, and this is where the beauty of this model comes in (as long as you are always expanding that group), sharing and asking.

Reducing that BLIND SPOT is all about ASKING, asking your group why they do something, asking for training etc. Even if you think you know something they do is wrong or not as efficient or safe as something else, you need to know what the reasoning is behind it.

Challenging that HIDDEN area is about DISCLOSING what you know and getting EXPOSURE. This means putting your thoughts and knowledge out there to help increase the knowledge of your group, but also as I touched on above that wider group/community. This will help highlight if what you know is correct or not, or if there is a different approach. As you do this you knowledge increases and you will learn about areas you didn’t even know existed. While you may not have the knowledge for these areas at first, you will now know they exist and that journey of DISCOVERY is underway.

To bring this process to life a little, I am going to take the subject of ‘Out of Air’. I am going to make a huge presumption that the majority of people reading this will have learned to keep the Octo/Alternative Reg in the imaginary triangle between your chin and nipples coming under the right arm. By speaking or talking to your initial group, you find alternative methods of attaching that Octo, magnetic clips as an example. By choosing a new Agency and going on a course, you will find some agencies teach the Octo coming off the other side of the 1st Stage. You learning and find that having the Reg coming off the opposite side offers greater flexibility when dealing with an OOA emergency. You go back and share this with the larger/extended group (ie through social media) to see if your knowledge stands up. Someone in that larger group then informs you of something called a long hose and primary donation, something you and your normal group knew nothing about! (Discovery). So you once again you go off and learn, increasing that known area. Then you go back to the larger group maybe challenging the idea of giving the Regulator you are breathing to an OOA causality. Someone in that group then highlights, with mixed gas diving, being open to someone snatching your Reg from your mouth could save your life, as you could end up breathing a dangerous mixture. What’s this about dangerous mixtures you ask and so the circle continues.

As a diver you have a few of choices;

1) Assume you know everything and enjoy your camp on top of mountian.

2) Accept that you do not know everything, but happily stay in the KNOWN area.

3) Accept that you do not know everything but work to expand that knowledge.

Choice 3 can be challenging and hard, especially at first. As I said near the start I thought I knew a lot, even now on easy dives I find it easy to fall into area of I know everything. I do try and battle this, by always trying to find out something new, even if it’s a simple question of asking a buddy why they have kit setup a certain way. I sometimes try to do something different such as take a different approach to the dive briefing, all in hopes I can learn something, and prove I am no longer on Mount Stupid :-).

Thanks for reading, I hope you got something out of it! Let me know either way.

G-SAV

Normalisation of Deviance

Let me start by putting my biases out there, I have fallen in love with this term. It is so simple but yet so powerful and it has been really interesting furthering my knowledge on the subject. Normalisation of Deviance was a term coined by NASA following investigations into the Challenger explosion. There are a number of YouTube videos on the subject and I would highly recommend watching them.

Let’s first examine the phrase ‘Normalisation of Deviance‘ and what it means.

Normalisation: a process that makes something more normal or regular.

Deviance: diverging from usual or accepted standards

The term fits very well with human nature to look for shortcuts and efficiency savings. As humans we are very good at identifying short cuts and rationalising them. These traits easily transfer into Diving.

In diving, we have a number of set procedures and guidelines we are taught to make diving as safe as possible. Now some of these vary from agency to agency, but there are many generic ones, and even the ones that vary have similar underlying themes and reasoning’s. For this example let’s take the Buddy Check. Agencies teach in different ways with different acronyms but the underlying reason is still the same, where the main diving components are checked. Deviance is when divers move away from these procedures for example only completing a quick short buddy check (skipping bits) or not completing one at all. Divers are deviating away from procedures by taking these short cuts. When divers do this, and there are no incidents during the dive, the justification for the short cut is reinforced, and this shortcut is then taken again and again, then starts to become the norm, ‘Normalisation of the Deviance‘. The key phrases heard are, ‘It’s always been fine’ and ‘Never had a problem’.

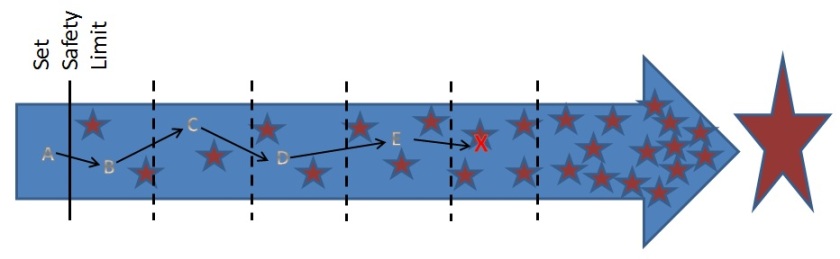

The graphic below is a representation of the scope and dangers of a dive. As it advances the chances of incidents illustrated by red stars increases, all the way to the point where an incident is inevitable. Now as divers it is impossible to know where these incidents sit or will appear, all we know is there is a “safe zone” (for this article I am going to refer to it as the safe zone, but it is not completely safe) where incidents are extremely rare and the various agencies have created procedures to help divers stay within this zone. Depth limits are an example of this.

Now take a diver who ignores/skips one or more of these procedures and moves from point A to point B without incident. After a few dives they personally shift their view/perception of the safe zone along and this becomes their new benchmark as everything has been fine so far. Once a shortcut has been taken, it is human nature to look for the next, and this moves the diver to point C and eventually their benchmark is reset again. This happens in incremental stages all the way along until the diver hits an incident (Red X). At this stage and evidenced in many discussion topics on various online forums, the divers justification and root cause analysis is that it was that last small change they made that caused the incident, that extra shortcut from point E. While everyone else looking in from the outside are not surprised as the distance between being in the original Safe Zone and X is huge.

Now take a diver who ignores/skips one or more of these procedures and moves from point A to point B without incident. After a few dives they personally shift their view/perception of the safe zone along and this becomes their new benchmark as everything has been fine so far. Once a shortcut has been taken, it is human nature to look for the next, and this moves the diver to point C and eventually their benchmark is reset again. This happens in incremental stages all the way along until the diver hits an incident (Red X). At this stage and evidenced in many discussion topics on various online forums, the divers justification and root cause analysis is that it was that last small change they made that caused the incident, that extra shortcut from point E. While everyone else looking in from the outside are not surprised as the distance between being in the original Safe Zone and X is huge.

Now this problem is normally compounded due to the fact that human nature makes us followers in short cuts. What you find, groups of divers move through these steps together almost in their own bubble as these shortcuts become the social norm. When others witness this group, they rarely if at all, point out the issues and more often than not, are influenced into taking the same or similar shortcuts. The cycle then repeats itself drawing in more and more divers.

A common example of this outside of diving is driving cars, how many of you reading this break the speed limit and carry on doing so because nothing happened? How many like to but are careful as don’t want to get a ticket, but when someone comes shooting past, you then speed up to follow them thinking they will slow/be first to be pulled over if there is a speed trap or the police? If you look at the statistics your chance of crashing / causing an accident is greatly increased once you go beyond this speed limit. Drivers then also justify driving fast by claiming to being good drivers, but how many have actually done an advanced driving or high speed course? FYI, I am not admitting to anything and take from it as you will, but I will clarify, I myself are human. 🙂

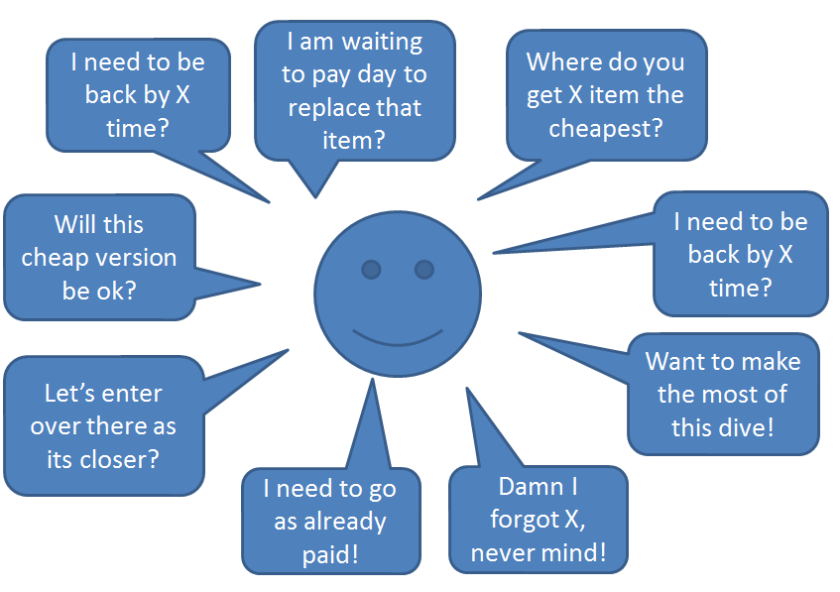

So why do divers do it? There are a number of factors that push / encourage humans to constantly seek out shortcuts. The main one is shortcuts in general are extremely positive, our whole evolution of a species has benefited hugely in the desire to find and take shortcuts and this has led to huge advancements. We are consciously and unconsciously taking shortcuts day in day out. The difference being is the failure of the majority of shortcuts very rarely have any significant impact on us. So as a natural state, it is something extremely difficult to fight and for this reason, it is far easier to fight it as a group then as an individual. The challenge for the group is to fight this urge, otherwise as mention above the group could cause actually swing it the other way. The other 2 big influences are time and cost. We only have a set amount of time to enjoy our diving along with a set amount of cash to fund it. These all play such a huge roll, even when people deny them playing a role in their decision making, they do. How many times have you heard some of the following comments from divers or you have used yourselves?

Now I am not implying these are bad comments to make, as sometimes they are completely reasonable things to say, suggest and do. The point is how the factors above do affect ‘everyone’. I am sure you can also think of a lot more examples.

So how do we tackle this issue in our own diving and diving communities?

First I think it is good to try and categorise these deviance’s, and I think most can fit into 1 of 3 categories.

1) Unintentional Errors (Mistakes, Slip ups)

These deviance’s from procedures/protocols are made by accident, and the diver is normally quick to self-correct themselves initially. However we are very much creatures of habit, and the more the unintentional error repeats itself, the more likely it will happen again and again. We are never 100% perfect, but one way to help this is with notes/check lists. For example making notes from a dive briefing will help cement the information further, or having a setup check list. Aviation/Pilots are a great example for this, even if they have been flying the same plane for years, doing multiple take offs/landings each day, they still work through a check list.

2) Risky Behaviour (Risk is underestimated or believed to be justified)

This is probably the most difficult ones to tackle or recognise as everyone’s view/estimation of risk is different, also the level of risk is greatly influenced by a divers skill set. These deviance’s are the ones that slowly build up over time, and therefore are the more difficult to tackle. I touched a little bit on this in a previous blog:

https://grahamsavill.wordpress.com/2017/08/05/better-way-to-dive-to-be-a-better-diver/

3) Reckless (Disregard of Risk or Negligence)

There will be multiple deviance’s away from many if not all protocols, and the diver will have little to no regard to the dangers or consequences of this. Divers who fall into this category will unlikely listen to reason or believe they know everything anyway. The good thing for other divers is, this is very easy to spot, and our human nature is to stay away from risk, so we naturally try to distance ourselves from these divers. Most of the time the only way for these divers to change their view is when they are confronted with an actual incident. As nothing can convince the divers in question, it’s important to highlight the issues to new divers who maybe listening/watching so they are not influenced by bad practice.

Next step is to decide in our own dive groups what our procedures and protocols are. The great part here, is the majority of the hard work has been done for us by the various agencies. Now as mentioned above, these protocols can differ from agency to agency and it’s up to the group to decide which one they follow.

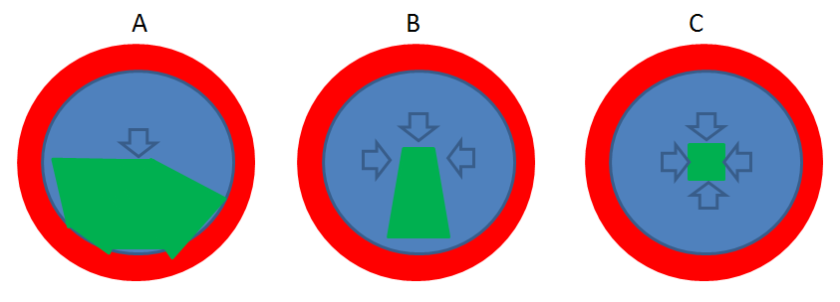

If we look at the graphic above we have 3 groups of divers A,B and C. The red area indicates the danger zone where incidents turn major, the blue is the safe zone, green represents where an incident could progress to, and the arrows represent protocols. These groups are not definitive, and are based more on a spectrum, so would say these represent the two extremes and the middle of that spectrum.

Group A, are following the very basic of protocols if any at all, and in an event of an incident, it can progress and escalate in a number of directions, as each diver will have no real indication how the other divers will deal with the situation. You see this regularly on dive holidays where you have a number of divers who may have never dived with each other before, who get a basic dive brief, then follow a guide around a dive site. Here you find only the simplest of protocols have been discussed or addressed.

Group B, have a number of protocols in place but differ slightly. When an incident occurs, majority of the incident is contained by these protocols and there is only a small area in which the incident can evolve outside of their protocols. This is where the majority of regular divers sit who have regular buddies, they have a good understanding of what each of them will do in an incident and would have the majority of protocols covered. However things will be different from diver to diver which will change their response to an incident such as the equipment they are using (Singles, Sidemount, Twinset, Rebreather, BCD v Wing, Spool v Reel, Different Gas Mixes etc).

Group C, have very strict detailed protocols in place, and when an incident occurs, taking out the human factor, their response will be exactly the same. This means the chance of the incident evolving is limited as much as possible (just to note, this does not mean it is impossible, just less likely). This was very much the DIR (Do It Right) philosophy, where they went with protocols such as matched equipment setup, out of gas, specific gas mixes etc.

Now you have a better understanding of these groups, have a think about some of the following incidents and how the divers in group A could all do something different when the incident occurs and how that could impact the incident by making it worse. Out of Gas(Primary/Secondary Donation), Separation, Dive Time/Depth Overrun, Poor Communication, Entanglement, Loss of Viz, Group Position in the water.

The size of the group plays a large part and I see a lot of debate around how many divers should make up a group, from people claiming diving solo in a group, to others saying buddy pairs, and Tec divers claiming teams of 3. As the vast majority of divers sit in groups A and B, imagine the possible issues as more divers are added to a group incident each with their own individual protocols. For these groups buddy pairs are certainly the better way to go and is the reason many recreational agencies promote this style of diving. Now let’s take group C, imagine if the additional divers follow the exact same protocols and an incident occurs, having an extra 1 or 2 divers would certainly help and actually become a must have as you pursue more and more challenging dives. I want to take a quick moment to mention a gripe I have about people who talk about diving solo in a group of divers, overall which group above do you think that group is as it is clear they have different protocols? I also touched on this topic in a couple of my other blogs the one linked above and https://grahamsavill.wordpress.com/2017/10/07/diver-stages-from-reliant-to-contributing/

So to finish off this blog I wanted to leave you and your group with a few questions to consider the ‘Normalisation of Deviance‘ in your diving.

- What behaviours and conditions do you accept and dive now, that you previously would not accepted?

- Is all your kit maintained and serviced in line with manufactures recommendations?

- What shortcuts do you find yourself taking?

- Which rules do you change/flex so you can do that dive?

- Do you do in-depth analysis on what could have gone wrong or use Success of a dive to define what is acceptable?

- Do you focus on the incident that happen/nearly happened or what behaviours/protocols that were seen as acceptable before the incident?

- What changes have you made to the procedures you were taught as experience tells you these changes were fine to make?

- How does your group deal with members who raise issues/concerns?

I hope this blog has come across as informative and you have enjoyed my take on the subject. As always, I would love to hear others thoughts on the subject.

G-Sav

How to Use Less Gas While Diving

Recently I have seen a number of questions posed asking how can people improve their breathing rates aka reduce the amount of gas they use. I find it funny many people suggest options such as breath training devices, taking longer/deeper breaths, concentrating on your breathing, yoga breathing etc. All these work on the premise of addressing the issue of breathing, not the cause of why as a diver you need to breathe. Unless you have difficulty breathing while walking around on land, these are only going to have a small impact on your breathing rate and will take a reasonable time period to show any worthwhile results. What divers need to focus on, is the cause of the breathing, as this will have a greater impact on your breathing rate.

First off, it is good to actually quantify your diving breathing rate, commonly referred to as SAC (Surface Air Consumption) / RMV (Respiratory Minute Volume). I have written a blog on how you can calculate these here:

https://grahamsavill.wordpress.com/2017/07/26/gas-management-and-planning/

As humans on average take around 15 breaths a minute with a lung tidal volume of about 0.5litre when at rest, which is around 7.5 litres a minute. There is a rough formula of Body Weight In Kilo multiplied by 7mililiters to get a better average for your body type. Again these are averages, but will give you an idea.

The graphic below represents your lungs. The red area represents the your residual volume of your lungs once you have fully breathed out and cannot breath out any further. The Blue area represents your tidal volume, this is how much you breath in and out at rest. The Light Blue area represents your Vital Capacity, this is the total amount of air you can breathe in and out of your lungs. The black line represents the capacity you are using when your breathing pattern at rest then progressing on to when you experience exertion.

Second is a quick recap into why as humans we need to breathe, and in the most simplistic form, we need to breath in Oxygen for our organs to work, and need to breathe out carbon dioxide which is a by-product from our organs. The harder our organs have to work the more oxygen they need and the more carbon dioxide they make and need to get rid of. This equals to an increase in breathing rate and depth of breathing. For example compare your breathing sat doing nothing, walking round the house, to running/lifting something heavy. It is actually the level of Carbon Dioxide in our bodies that cause our reflex to breath. This means when you hold your breath, the urge to breath out and in, is not the lack of oxygen but the level of Carbon Dioxide. Free divers in simple terms learn to fight that reflex by building up a resistance to it.

There are 2 areas that make divers breath more, ‘Physical Exertion’ and ‘Mental Exertion’. We are going to have a look at what causes both of these in some more detail and how as a diver you can counter these. The simple formula is, Less Exertion = Less Breathing = Less Gas Used.

It is a very reasonable suggestion to suggest people will improve their SAC rates by just getting out there a diving, which is true to an extent as during those dives they will be unconsciously improving on these two areas. However by being aware of these and working to address them in a structured approach will simply increase the speed of improvements and lead to better results.

Now this is not a complete list, and many things will affect your breathing that are outside your control such as visibility, currents/tides, water temperature etc.

Physical Exertion

One of the biggest causes of physical exertion in divers is drag. As humans we can be fairly streamlined in the water, however once you add on all the scuba gear that becomes a different story. There are 3 areas that greatly effect drag, Weighting, Trim and Kit Setup.

Weighting

Be correctly weighted for every kilo of extra weight you add above what is needed is to be neutrally buoyant, you need to add air to your BCD/Drysuit to counter you sinking. This air displaces 1ltr of water, so if you are 3kg over weighted, that’s 3 extra litres of water you need to move as you move. The issue is then multiplied by many BCDs expanding outwards making them less streamlined harder to move through the water by creating drag. If you are not adding this extra gas to your BCD and you are over weighted, then you will be compensating for the negative buoyancy in your kicking which will cover further down.

Trim

To be the most streamlined in the water you need to be horizontal as you swim, and more importantly when you are stationary. If you are not horizontal when you are stationary ie find yourself naturally shifting to a vertical position (quickly, a very slow shift is fine), 2 things are happening when you swim. 1 your kicking is not effective, in the sense that some of the energy you have put into your kicks is not actually used to move your forward, but is actually being used to bring you into a horizontal position. 2 As you swim forward the water is actually pushing you into trim, which means your body is causing drag. Once you have your weight perfected, look at how you can spread the weight across your body, so when you stop swimming, you stay horizontal (In Trim).

Streamline kit

This is very much about removing as much drag as possible, less drag means less water resistance therefore less effort needed to move forward. One of the key things divers can change is the accessories they carry. When they kit up on the surface, these hang down the body, but as soon as they are horizontal in the water these hang away from the diver increasing drag. Some simple solutions are attaching items to the rear (around your bum) so they are in the slipstream of the BCD/Tank, putting items in pockets, or using bungee loops to hold the item in place. Other measures such as decreasing the length of hoses and securing them against the body can also help. This can also be done with the BCD inflator hose. Don’t forget your own body position in this as well, a common thing I see with divers is they cross their arms and let them hang down. If you do this now and look down you can see the amount of drag created, to see it in effect, next time you are in the pool push off the wall with this arm position and see how far you go compared to having your arms out in front. I am not saying this position is wrong, I am just pointing how body position can effect streamlining.

Efficient Kicking

When people learn to scuba dive they normally learn the flutter kick, while this can be a powerful kick, energy is used to push the water up, down and backwards depending on the part of the circle of the kick you look at. This is very much a continuous kick, so the muscles are worked a lot, so requires a higher breathing rate to get the needed oxygen to the muscles. This kick is seen as inefficient due to some of that kicking energy being used to push water down and up rather than all the energy being used to push the water backwards. This issue can also be magnified if you are incorrectly weighted and/or your trim is not horizontal as your kicking will be pushing more water downwards.

A more efficient kicking style is the frog kick. A little harder to master than the flutter kick, but this kick has two benefits over the flutter kick in terms of efficiency. Nearly all the energy in the kick is used to push water backwards, and second, the kick is normally followed by a glide which means you are not constantly kicking. Now I am not suggesting Frog Kick is always the right kick to use and there are other kicks out there and variations. In the context of this blog however, it means you actually use your leg muscles less, therefore needing less oxygen and carbon dioxide is created.

Now with any movement, it fits on a spectrum between Aerobic and Anaerobic activity. For this discussion we will be looking towards the 2 extremes and generalising a little as everyone’s muscle make up is different. At the Aerobic end, is movement that you do with a fair number of breaths, this means oxygen and carbon dioxide levels are managed with each breath, such as going for a light jog. Your heart and breathing increases a little, and when you stop you feel in control of your breathing. At the other end is Anaerobic which is fast movements where you take far fewer breaths. This causes a decrease in oxygen in the system and increase of carbon dioxide. Think of sprinting a short distance. At the end you need to catch your breath and your body works hard to re balance the gases as well as clear out Lactic Acid build up in the muscles. This will lead to the use of more deeper breaths to accomplish this.

So how does this relate diving, basically try to stay more to the Aerobic end of the movement spectrum, slow small movements where possible. Where possible move as least as possible, such as using small adjustments in your breathing to control buoyancy rather than always using your arm and hand on your BCD inflator. Rotate to on to your side and bend to look around rather than completely turning your body around in the water to then turn back again, or even more efficient simply bend the head down so you are looking back with your head upside down. Be mindful of your activity before entering the water, if you have had to work just to get to the water’s edge, you might be heading into that Anaerobic area, stop ‘catch your breath’ before starting the dive.

Exposure Suit

Basically choose the right one for you, and for the conditions you are diving. If you get too cold or too hot, your body will need to work harder to maintain the correct body heat therefore needing more oxygen.

The best bit about all this, is you can make changes to all the above in a relatively short period of time and see almost an immediate impact in your breathing rate. While it will take time to perfect each of the above, a vast improvement in each of those (minus frog kicking) can be done in a single dive. This is why when anyone raises the question about improving their breathing rate, this is my immediate go to response. I would suggest using a video camera to actually film yourself as it is a great tool, as many divers have never actually seen the way they dive and how they look underwater.

Mental Exertion

This is very much about the individual as we all react differently, but the aim is to stay calm. Now that is a lot easier said than done. I personally don’t get worried as I have been diving a long time, however I fall for the trap at the other end of the spectrum, of excitement. Excitement has a similar effect as being worried, your heart rate increases, therefore breathing increases.

However there are steps every diver can take around Mental Exertion and these evolve around task loading. As a diver if you can minimise your task loading you will reduce your mental exertion and which will decrease your breathing rate. Keep your kit simple, leave the gizmos at home, the more you have to think about/learn to use just adds to task loading. Keeping it simple also reduces failure points, less failure points, less likely something will go wrong, less to worry about.

Dive skills are also important and play a big part in Mental as well as Physical Exertion. Many skills can be done in a number of different ways/variations, but some are less exerting and more efficient than others. Skills should be practiced and rehearsed regularly. It’s important to remember “Practice Doesn’t Make Perfect! Only Perfect Practice Makes Perfect!”. By working on skills regularly will reduce task loading and exertion and have a positive impact on your breathing. Even skills that have been mastered can weaken over time if not used. If the excuse is the exercise/skill is easy, then simply make it harder for yourself, you will only get better because of it.

Plan your dives within yours and your dive buddy’s comfort zone and skill set, worrying about yourself and/or someone else during your dive will only increase your breathing (I am not saying ignore them or pretend they are not there!). I did touch on this subject a little bit in another blog: https://grahamsavill.wordpress.com/2017/08/05/better-way-to-dive-to-be-a-better-diver/

Last of all remember to breath, sometimes when we really focus on something we forget to breath, the issue here is the body shifting from that Aerobic to Anaerobic process.

A good way to help with Mental Exertion due to your own feelings is to focus on your breathing, now the breathing does not impact your exertion as much as the focusing does. This concentrated focus shuts off other stimuli (such as stress, worry, nerves etc), reducing mental task loading therefore reducing Mental Exertion.

Focusing on removing/addressing the cause of Exertion as listed above, will have the biggest impact on your air consumption.

If you are still not happy/not where you want to be after addressing the points above there are some additional things you can try. These are more dependent on the individual and often have little impact if done before addressing the things above and can take a while for any real progress to show through. First off fitness, the fitter you are, the more efficiently your body will work. If you want to get really picky the type of food and drink you have before you go diving will also play a part as they can increase heart rates, therefore increase breathing. Difficult to digest food, will mean your body is working harder. Yoga breathing exercises can actually help the mental exertion side, especially if you still find you are still suffering from nerves.

Most recreational regulators if serviced correctly should provide you with plenty of air, but if you find your regulator is making you work for your breath, then it might be worth getting the settings adjusted slightly.

As per other opinions out there;

Training devices, in my view have little to no impact to the recreational diver, as they are very much aimed at top athletes and even not all them use these things. As also mentioned above you would be better working on your overall fitness. Like many forms of training, you either have to continue training or actively use the muscles you have built up. So unless you are very active, when you stop using the device your body will slowly revert back to its norm undoing a lot of what was done.

Skip breathing is where you either have an extended pause before inhaling or exhaling, ie take one breath instead of two. The actual savings are either cancelled our or become negligible as carbon dioxide builds up quickly meaning more gas is needed to clear it. This breathing is also not natural, yes you could train yourself but ultimately you are having to think about your breathing, which in turn just adds to mental Exertion and task loading.

Last of all I wanted to touch on breathing patterns, and the suggestion of slower deep breaths. What happens with many divers, is they are normally dealing with a lot of unnecessary exertion due to the reasons above, and their breathing pattern goes to quick and shallow almost like a pant in the extreme circumstances. This is a natural reaction of the body to get oxygen in and carbon dioxide out as quickly as possible. This can also be seen after exercise, with the solution being to resist panting and take deeper breaths. These bigger deeper breathes work well at shifting large volumes of gas and are more efficient then the panting. This is why many divers believe this is the answer to consuming less gas while diving. What has actually happened is you have improved the efficiency of your breathing for the exertion you are experiencing. It is a solution for the symptom but not the cause, as the exertion is still there, so you will still be using more gas then is necessary for that dive.

To sum it up, focus on the causes of exertion rather than how to breath and you your body will naturally sort out the breathing.

Thanks for reading, please check out my other blogs.

G-SAV

Diver Stages – From Reliant to Contributing

In my view there are 4 stages of diver development that sit outside the normal core diver training programs. Even though I believe these sit outside these programs, these stages are very much interlinked with training and in some instances a necessity to advance.

In this blog, I wanted to discuss these stages in a little bit of detail to give you an overview. I am planning on expanding on this concept in further blogs and cover them off individually. 3 of the stages are very much a linear progression from one to the next; Reliant-> Self Reliant -> Contributing. The 4th Solo branches off after the Self Reliant Stage.

Disclaimer, just because you move up a stage or 2 does not mean you will always stay at that stage for every dive you do. There are 2 things that effect this, 1) Your kit set up for a particular diver. 2) The complexity of the dive itself. For example, there are a lot of dives where I would class myself as a ‘Contributing Diver’ however if I am doing a progression dive where I am expanding my own experience, I would most likely slip into the ‘Self Reliant’ stage. If I am on a beach dive (where I leave the redundancy equipment at home) or if on a course, learning and experiencing something completely new, the chances are I will be very much back to being a ‘Reliant’ diver.

Now it’s important to try and understand what stage you are at for each individual dive, but also just as importantly what stage your buddy is at, as well as any other members of your group. This knowledge will give you a greater understanding of the limits of the dive and what are the most probable outcomes/solutions to any problems/issues that may arise on the dive. This will help in making the most realistic dive plan.

Reliant (Dependent) Diver

This is where all divers start and where many stay. This is not a bad thing, it just limits the dives that can be done safely. Divers are very much reliant on their buddy as a source of control, leadership, equipment redundancy and problem resolution. One of the core issues with reliant diving is if there is an issue, the diver in problems is actually taking something away from their buddy! Be that equipment, gas, and thought process (Basically the other diver needs to concentrate on helping their buddy while also trying to concentrate on their own diving). This greatly increases the risk. Some of the common ways these risks are mitigated by these divers is; limited depth, diving more as a group, less challenging dives etc.

Self-Reliant Diver

Becoming self-reliant is a big step, as it involves a large shift in mindset around control and problem resolution. There is also the addition of redundancy equipment. The challenge for a self-reliant diver is to not forget about their buddy or dive group, this is not solo diving. This is one of the biggest issues I see with self-reliant divers, they are paired with a buddy or group on the surface then when they enter the water they act as if it is a solo dive and all the buddy protocols go out the window. This is extremely dangerous when their buddy or group is made up of Reliant Divers, and even with a self-reliant buddy, not all situations can be dealt with alone. The basic concept around being self-reliant is if you have an issue, you are no longer taking anything away from your buddy because you have a set skills and equipment to deal with it. This is what normally happens, the diver has an issue, they deal with it while their buddy waits on hand to offer assistance.

Solo Diver

In solo diving you are completely alone and there comes the greatest risk. It is the understanding of the situations you will not be able to deal with alone that if you get caught in you will die. Now just because a diver goes diving by themselves does not mean they are at the Solo stage in my view. I have known plenty of divers who fit into the reliant stage but are happy to put on the same standard basic equipment and go diving by themselves. In my view the biggest shift from the other 3 stages is identifying the risks that could now kill you, and how focused you must be not to fall foul of them. Nothing brings this home like your first solo dive, when you find out what being alert actually means and you realise how much you rely on other divers subconsciously. What could be considered as a normal risk when diving as a pair now becomes a life and death one. Once you have had this heighten awareness and experience it on a regular basis it becomes difficult to shift and when you go back to diving with a group or buddy.

There are a couple of arguments I see made around either Instructors while instructing being solo or a qualified diver diving with a less qualified experienced diver, this is wrong in my mind, as if something happens your students/buddy will try and help, and there is a high possibility they will get you to the surface. There is also a high chance you can direct them to assist in resolving the situation. As mentioned above in Solo diving you only ever have only yourself to rely on.

Contributing

This is when you have a diver who is self-reliant but has further skills, knowledge and equipment to add to a dive. A lot of the time you find a Contributing diver diving with divers at a lower stage, so many of the benefits cancel themselves out. But what if you have a couple or a group of Contributing divers diving together? Now this is where the real magic happens and what true team diving is all about. It is all about the Synergy of the team such as the sharing of leadership during various portions of the dive. When an issue arises, as the diver deals with it, the others are already on hand ready to assist or are already doing so, and already taking the next steps. Synergy of the divers makes this very different to two reliant divers diving together. Aristotle’s quote ‘The whole is greater than the sum of its parts’ very much comes into play here. This level of diving is normally learnt when Divers progress into the Technical arena. Having said that, there is no reason why Recreational Divers can not reach this stage.

Being truthful about where you and your buddy sit in relation to these stages, and planning dives around this, will lead to safer dives.

I hope this article has given you a reasonable overview of where my thoughts are on this subject, and as mentioned will be looking to expand on these individually in later posts. As always would love to hear others views and thoughts on this.

G-SAV

Better Way To Dive, To Be A Better Diver

What is the ‘Better Way To Dive’?. Now I have used ‘Better Way’ rather than ‘Right Way’ as I don’t think forcing something on people works, especially when some of the points don’t match up with what they have been taught in their courses. This is one of diving’s major hurdles, as many divers take what they have been taught as gospel. Now a lot of the time the instructor is not entirely incorrect and what they are teaching was correct at one stage/time or unaware of a more efficient process. The best examples of this is 1) the quarter turn back when opening the cylinder, 2) Proper buoyancy control and trim.

Now as diving has increased in popularity 2 things have happened;

1) The amount of research being carried out within diving has greatly increased around practices and equipment.

2) The recording of incidents and root cause analysis has also improved leading to better data for point 1 above.

Now we can’t make divers change or improve, as the desire to do that comes from the individual as the way we reason is different. So I am going to try and share my views in a way that it will hopefully get people thinking about their own diving in a similar way to my previous and future posts. So don’t worry I will not be telling you how you should be diving.

First my disclaimer! Having been diving for 23 years, I can admit, I have not always been a good diver, and are guilty of the many things I have now started to post about. What changed for me, was my attitude around risk and my naivety that I believed I was a good diver in skill and knowledge. One of my favourite quotes I heard was ‘At 50 dives I thought I knew everything, at 250 I realised how wrong I was!‘. My risk acceptance changed for me as I grew older, slightly more wiser and very much in recent years when I started a family. Also as I progressed, expanded my diving and I meet a few divers who reset my perception of where the bar was set to be seen as a good diver. I am a competitive person by nature, so this gave me a major boost to try and be better. I now do a lot of reading/research on world class divers and trying to increase my own knowledge. I am currently reading a couple of instructor manuals on Ice Diving, now where I live, there is no ice so no courses but I have that desire to learn something new and gain a new perceptive.

Second is my little rant, throughout my diving life, I have heard and used the phrase ‘There is more than one way to do it’ which I agree with. However it does frustrate me, when it is used to justify a dangerous practice or view point, especially when that view point is being pushed on to new/inexperienced divers. It’s a bit like the phrase ‘That’s how I have always done it, and it’s been fine’. There is always more than one way to do something, but each one comes with its own Pro’s and Con’s and its how these balance out that really matter.

So let me break down what I mean by ‘Better Way To Dive. “Safety”, “Simplicity”, “Effectiveness” – all while being affordable. This is very much in essence on the best way for you to dive as an individual.

Affordability:

We all have to start our kit collection somewhere and majority of divers cannot afford the best kit, so my view is whatever kit you buy understand it’s limitations and stay within them. How many of you know your regulators max operating depth or minimum water temperature?

Understand what you Must Have, Should Have and Could Have. This can be difficult due to the vast amount of information out there and will require you to do some research. I normally listen more to divers who fit some of the following criteria; Moved from Recreational to Tec Diving, Are Multi Agency, Dive Different Environments, Dive With Multiple Clubs/Groups. This means on average they have wider experiences then a recreational diver who has had the same instructor for every course and dives the same sites and conditions. However another disclaimer, we all know there is always at least one person who bucks a trend.

So with the above in mind try and get kit in that order, and if you are going to be buying higher end models focus on the Must Haves first. No point in having a high end £800+ multi gas computer if you don’t have the kit to support those types of dives, when a £150 computer will do, and the difference could buy a better set of Regulators or Buoyancy Device, the main life supporting systems. Carrying on this example of the dive computer if you used the money on the must have kit, you only need a couple of cheap bottom timers and slate to use the kit to its full potential. Try to use money wisely and buy for the long term. The amount of money I have wasted on gizmos and the latest must have thing makes be cry! Like the fishes we love to swim with, we are all attracted to nice new shiny objects. This can sometimes be challenging because of costs, so try and work out a little road map on where you would like to take your diving, this will better help you plan your development and what kit you will need when.

Safety:

This is one of the biggest reasons we decide to attach 20+ kilos (44+ pounds) of kit to ourselves then jump in water to deep to stand in. We ‘feel’ safe and here lies one of the issues. Safety is based on our own perception and knowledge which sometimes can be fairly limited. A good diver is always questioning is what they are doing/using is the safest option. If you ever hear a diver talking about something being unsafe, all I can say is listen and understand why they think that as they will always be right as that risk exists! It will be down to your own views and opinions on how big that risk is to you. An average diver will decide if the risk outweighs the reward or not to them. A better diver will multiply that risk to themselves and others around them against the reward to themselves. An example, let’s say the risk is 1 point but the reward is 2 points. You could say the reward outweighs the risk. However if you take your buddy into account its now 2vs2 if they don’t completely feel the same way. If you then consider a group of divers (4), the risk could now be stacked 4vs2. A common real life example I see, is in buddy pairs were one diver has a bailout out bottle and the other doesn’t. In this case it’s not uncommon for the bailout bottle diver to push the dive to his limits (as he feels safe) but is dragging his buddy beyond his. This line of thinking should also goes beyond your buddy and group but to the people supporting the dive and the environment itself. The more of those factors you take into account the better diver you will be.

Simplicity:

Task loading is a big challenge for divers and becomes more challenging the deeper we go due to the effects of narcosis. Our brains work like computers, when they do too much, they crash. Now these crashes can materialise in divers in a few of different ways.